Blanching is a basic cooking method used to briefly expose food, most often vegetables, to high heat, followed by rapid cooling. It’s not meant to cook ingredients fully. Instead, blanching prepares them for their next use by stabilizing color, softening texture slightly, and stopping unwanted changes before further cooking or storage.

Home cooks most often encounter blanching when working with vegetables that need to stay bright, crisp, and clean-tasting. It’s commonly used before freezing vegetables, before adding them to salads or cold dishes, and before finishing them with another cooking method such as sautéing or stir-frying. Many restaurant-style vegetable preparations rely on blanching as a quiet but essential prep step.

The reason blanching matters comes down to control. Used correctly, it helps vegetables keep their natural color, maintain a pleasant bite, and behave predictably during later cooking. Understanding what blanching does, and what it’s meant to accomplish, allows cooks to handle vegetables with more confidence and avoid dull color, mushy texture, or uneven results.

Clear Definition or Core Concept

What Blanching Means

Blanching is a preparation method in which vegetables are briefly exposed to intense heat, then cooled immediately. The purpose is not to cook the vegetable fully, but to change its behavior, stabilizing color, softening texture slightly, and stopping natural processes that can affect flavor and appearance.

At its core, blanching works in two connected phases.

First, the vegetable is exposed to very hot water. This brief exposure to heat triggers visible changes, especially in color and firmness. The vegetable begins to relax without breaking down.

Second, the vegetable is cooled quickly. This cooling step halts the effects of heat so the vegetable doesn’t continue cooking on its own. Together, these two phases allow the cook to make controlled changes, then stop them precisely.

Blanching is less about time and more about intention. It’s a way to prepare vegetables so they behave predictably in whatever comes next.

What Blanching Is Not

Blanching is often confused with other cooking methods, but its purpose is different.

- It is not boiling. Boiling is meant to fully cook food until tender. Blanching stops well before that point.

- It is not steaming. Steaming cooks gently and continuously, while blanching uses a brief, intense heat followed by immediate cooling.

- It is not par-cooking. Par-cooking partially cooks food so it can be finished later. Blanching may prepare vegetables for later use, but its goal is control, not doneness.

The term can sound technical, but the idea behind it is simple: introduce heat just long enough to create specific changes, then stop those changes completely. Understanding this removes much of the intimidation and helps clarify why blanching appears so often in vegetable preparation.

Why This Matters in Cooking

Impact on Flavor

Blanching helps vegetables retain their natural flavor by limiting how long heat is allowed to act on them. Brief exposure to high heat reduces sharp, grassy, or overly raw notes that can dominate certain vegetables when eaten uncooked.

At the same time, blanching prevents the prolonged cooking that dulls sweetness and mutes freshness. The result is a cleaner, more balanced vegetable flavor, one that tastes bright without tasting raw.

This is especially noticeable in vegetables with strong natural compounds, where blanching softens intensity without stripping character.

Impact on Texture

When vegetables are heated, their cell walls begin to relax. Blanching initiates this change gently, loosening the structure just enough to improve bite without breaking it down.

Because the heat is stopped quickly, the vegetable does not continue soften. This creates the familiar crisp-tender texture associated with well-prepared vegetables — firm but yielding, never limp or mushy.

Understanding this helps explain why blanched vegetables behave better later. They bend rather than snap, yet still hold their shape.

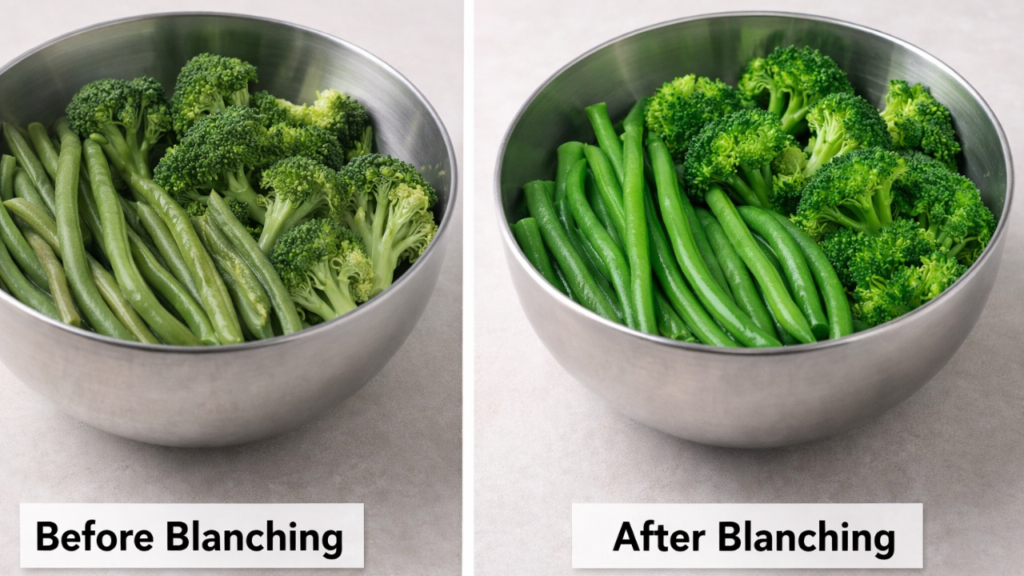

Impact on Color

Color change is one of the most visible effects of blanching. Brief high heat intensifies green pigments, making vegetables appear brighter and more alive.

If heat continues too long, those same pigments dull and fade. Blanching works by activating color, then stopping the process before it turns negative.

This is why blanched vegetables often display the vibrant green associated with professional kitchens. The brightness is not decorative; it’s a signal that the vegetable was handled with control.

Impact on Confidence

Blanching gives cooks a clear point of control. It defines a moment when vegetables shift from raw to prepared, ready for whatever comes next.

Knowing that a vegetable has been blanched allows a cook to move forward with confidence, whether finishing it later, combining it with other ingredients, or storing it without uncertainty.

Instead of guessing whether something is underdone or overcooked, blanching creates predictability. The vegetable has been stabilized, and the next step becomes easier to judge.

How It’s Used in Real Recipes

Common Cooking Situations

Blanching often appears as a quiet preparation step that happens before the main cooking begins. Many recipes rely on it to set vegetables up for faster, more controlled finishing.

In sautéed or stir-fried dishes, blanching is used to prepare vegetables so they cook evenly once they hit the pan. Because their structure has already been stabilized, they heat through quickly without losing color or turning soft while other ingredients finish.

Blanching is also common in salads and cold dishes, especially for vegetables that are too firm or bitter when raw. In these cases, blanching softens texture and tames intensity while keeping the vegetable fresh and clean-tasting.

Before roasting or grilling, blanching can help ensure vegetables cook through without overbrowning on the outside. This allows the final cooking method to focus on surface flavor rather than internal doneness.

Common Cuisines and Dishes

In French-style vegetable preparation, blanching is frequently used as part of mise en place. Vegetables are prepared in advance so they can be finished quickly with butter, herbs, or sauce while maintaining bright color and precise texture.

In many Asian kitchens, blanching is used to prepare vegetables ahead of stir-frying. This allows fast, high-heat cooking without overcrowding the pan or overcooking delicate ingredients.

Mediterranean vegetable dishes often rely on blanching for salads and composed plates, where vegetables need to be tender yet vibrant. The goal is a clean flavor and a texture that holds up well with olive oil, acids, and herbs.

| Cuisine | Where Blanching Appears | Why It’s Used |

|---|---|---|

| French | Vegetable mise en place | Preserves color and allows quick finishing with butter or sauce |

| Asian | Stir-fry preparation | Ensures fast cooking without overcooking or pan crowding |

| Mediterranean | Salads and composed vegetable dishes | Creates tender texture that holds up to oil, acid, and herbs |

Across cuisines, blanching serves the same role: preparing vegetables so the final dish is easier to control and more consistent.

How to Apply It at Home

What to Watch For

- A noticeable shift in color, especially in green vegetables, from dull or muted to more vivid and alive

- A cleaner, more uniform appearance across the surface

- A slight relaxation in structure, where vegetables look less rigid but still defined

These visual changes signal that the vegetable has responded to heat without breaking down.

Sensory Cues

- Brightness: The vegetable appears more vibrant and fresh rather than opaque or faded

- Tender resistance: When touched, it yields slightly but still pushes back, rather than feeling soft or fragile

- Steam behavior: Steam rises quickly and cleanly, indicating strong heat contact rather than slow warming

These cues help confirm that the vegetable has reached the intended point of preparation.

Decision-Making Tips

- Blanching improves results when vegetables need to stay bright, crisp, and retain their texture through later cooking or serving.

- It’s especially helpful when vegetables are ready to finish quickly, combined with other ingredients, or used cold.

- Blanching is often unnecessary for vegetables that will be cooked for a long time or intentionally broken down.

- The moment to stop is when visual brightness and slight tenderness appear together, before softness develops.

The goal is not doneness, but readiness. Once the vegetable shows clear signs of change, its role has been fulfilled.

Common Mistakes & Misconceptions

Treating Blanching as Boiling

One of the most common mistakes is assuming blanching is simply boiling vegetables for a short time. This leads to vegetables being cooked too far, losing both texture and color.

This happens because the purpose of blanching is misunderstood. It is not about tenderness or doneness, but about controlled change. When blanching is treated like boiling, that control disappears.

Reframe: Blanching prepares vegetables; it does not finish them.

Skipping the Cooling Step

Another frequent misconception is that cooling is optional. When vegetables are not cooled promptly, they continue to cook from residual heat even after being removed from hot water.

This often results in vegetables that look correct at first but quickly turn dull or soft.

Reframe: Cooling is not an extra step; it’s what defines blanching as a method.

Expecting Full Cooking

Some cooks expect blanched vegetables to be fully tender and ready to eat on their own. When they aren’t, blanching is seen as ineffective or incomplete.

This expectation comes from confusing blanching with par-cooking or steaming.

Reframe: A blanched vegetable should feel prepared, not finished.

Using Blanching for Every Vegetable

Blanching is sometimes automatically applied, even when it provides no benefit. This can mute flavor, wash out character, or create unnecessary work.

Not every vegetable needs its structure adjusted before cooking.

Reframe: Blanching is a tool, not a default.

Relying on Time Instead of Observation

Focusing on how long blanching takes rather than what the vegetable reveals often leads to inconsistent results.

Vegetables vary in size, freshness, and density — time alone cannot account for those differences.

Reframe: Visual and tactile cues matter more than the clock.

Visual or Technical Breakdown

What Happens During Blanching

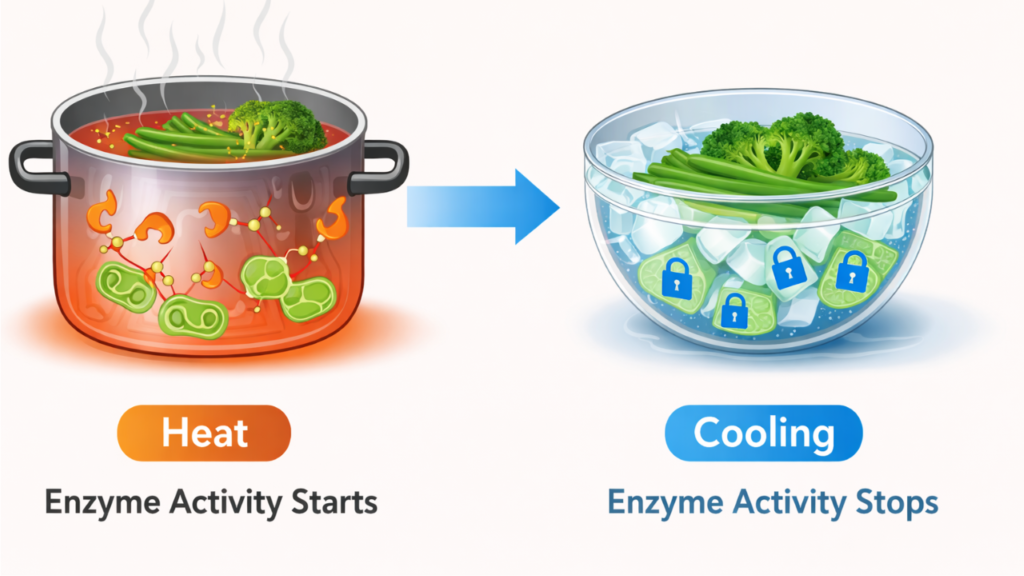

When vegetables are exposed to high heat, internal enzymes begin to react. These enzymes are naturally present and continue working even after vegetables are harvested. Over time, they contribute to dull color, flavor loss, and texture breakdown.

Brief exposure to intense heat slows or deactivates many of these enzymes. This is one of the key reasons blanching is used before freezing or holding vegetables for later use. The heat creates a controlled interruption in those natural processes.

However, heat does not stop acting the moment vegetables are removed from hot water. The internal temperature remains high, and enzymes can continue to alter texture and color if nothing intervenes.

This is where rapid cooling becomes essential. Cooling halts enzyme activity and prevents carryover heat from pushing the vegetable past its intended point. Without cooling, blanching turns into overcooking.

Conceptually, blanching works like a switch:

- heat turns specific changes on

- cooling turns them off

Used together, these two forces allow the cook to influence color, texture, and stability without fully cooking the vegetable.

This balance, brief activation followed by immediate control, is what makes blanching effective and repeatable.

When to Break the Rule

Blanching is useful, but it is not always the best choice. Knowing when not to use it is part of cooking with intention rather than habit.

Some vegetables lose character when blanched. Delicate greens, tender herbs, and raw vegetables can become muted or waterlogged when exposed to heat, even briefly. In these cases, freshness and texture are better preserved without blanching.

Blanching may also be unnecessary when vegetables will be cooked for a long time. Slow braises, soups, and stews already require extended cooking time, making early preparation redundant. The final texture and flavor will be shaped by the longer cooking process instead.

There are also situations where direct cooking produces better results. High-heat roasting or grilling can benefit from vegetables being added to the pan or grill raw, allowing surface browning and deeper flavor development that blanching might reduce.

Breaking the rule doesn’t mean ignoring technique; it means choosing the method that serves the outcome. When blanching improves color, control, and consistency, it earns its place. When it adds extra handling without benefit, it can be skipped with confidence.

Understanding this distinction allows cooks to use blanching deliberately rather than automatically.

Quick Takeaways

- Blanching is a preparation method, not a way to cook vegetables fully.

- It uses brief heat followed by cooling to create a controlled change.

- The goal is better color, cleaner flavor, and reliable texture.

- Visual and tactile cues matter more than time.

- Blanching is a tool. Use it when it improves results, skip it when it doesn’t

FAQs

Is blanching the same as boiling?

No. Boiling is meant to fully cook food. Blanching uses brief heat followed by cooling to create specific changes without cooking the vegetable through.

Do all vegetables need blanching?

No. Some vegetables benefit from blanching, while others lose texture or flavor. It’s a situational tool, not a requirement.

Why do recipes call for blanching before freezing?

Blanching slows natural enzyme activity that continues even in frozen vegetables. This helps preserve color, flavor, and texture during storage.

Can blanching be skipped?

Yes. If blanching doesn’t improve the final result or adds unnecessary handling, it can be skipped with no downside.

Does blanching remove nutrients?

Some water-soluble nutrients may be reduced slightly, but the overall impact is small. In many cases, preserving color, texture, and usability outweighs the loss.

Closing & CTA

Blanching is not about adding complexity to cooking. It’s about understanding how vegetables respond to heat and learning when a small adjustment can make a meaningful difference.

When you recognize blanching as a preparation tool, not a rule, it becomes easier to decide when to use it and when to skip it. That awareness leads to better color, cleaner flavor, and more consistent results in everyday cooking.

If you’d like to continue building that kind of kitchen understanding, explore more Kitchen Know How lessons as the library grows.

Kitchen Know How is written and curated by Cem Berkoz.